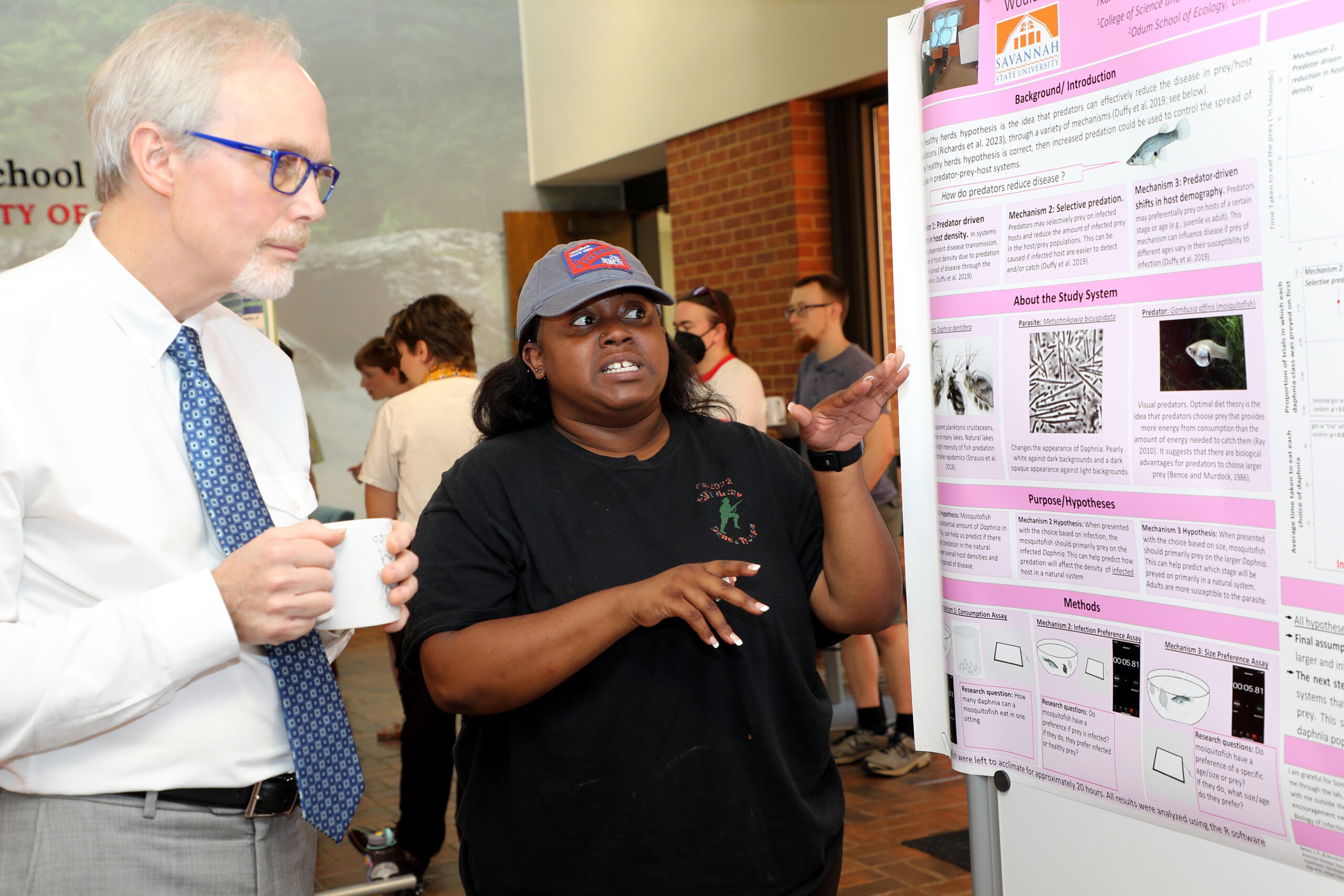

When T’Kai Adekunle first took an ecology class at Savannah State University, she knew she wanted to explore the field more.

“I wanted to use what I had just learned for something in the summer, to see if that’s something I wanted to go into,” said Adekunle, a third-year SSU student majoring in biology. She had an interest in both human health and ecology and found that the Population Biology of Infectious Diseases REU program, led by two Odum School of Ecology faculty, was the perfect way to expand her understanding of both fields.

“It may not be about people, but there are still concepts I took away from the program I can use,” she said. “A lot of these concepts can be tied back to human diseases and how they spread through populations.”

The ABCs of REUs

REUs, or Research Experiences for Undergraduates, are programs funded by the National Science Foundation that provide students an opportunity to perform research in different scientific fields. The Odum-based program aims to expose students to mathematical and computational techniques that can be incorporated into infectious disease research.

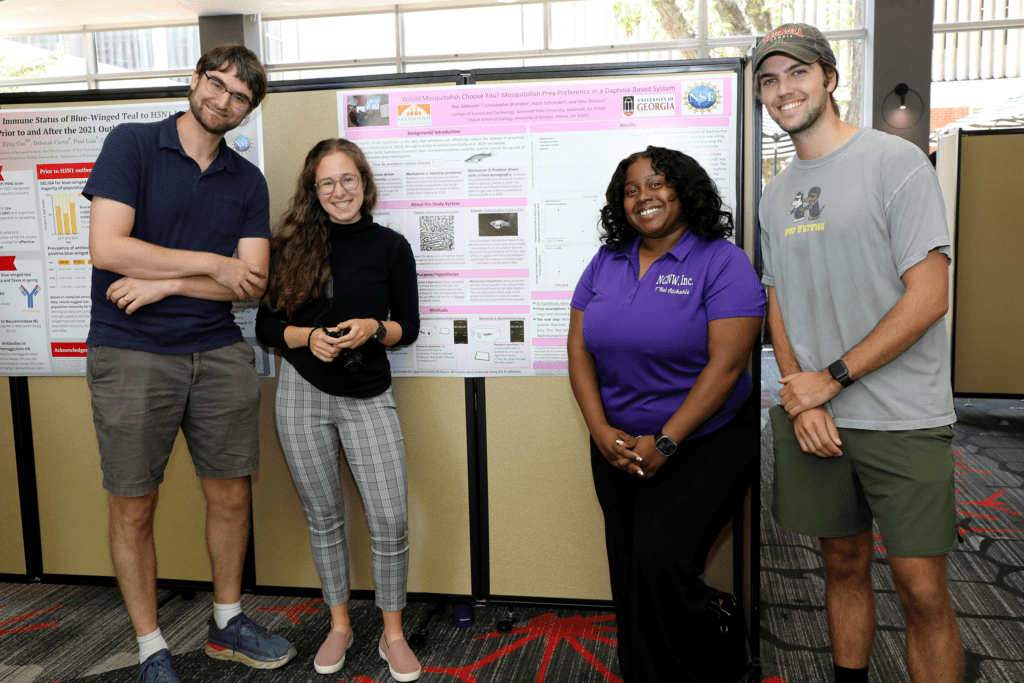

The Population Biology of Infectious Diseases REU program has offered students research experience in disease ecology for 11 years. Originally developed and led by John Drake, director for the Center of the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, the nine-week program prepares students for future careers in research and includes activities like coding workshops, journal clubs, lectures, faculty-hosted dinners and a field trip to the Centers for Disease Control. Faculty mentors propose research projects for the REU program, and when students arrive in May, they collaborate with their mentors to shape the projects’ questions and experimental designs. Students then work on their research throughout the summer, presenting their findings at a symposium in late July.

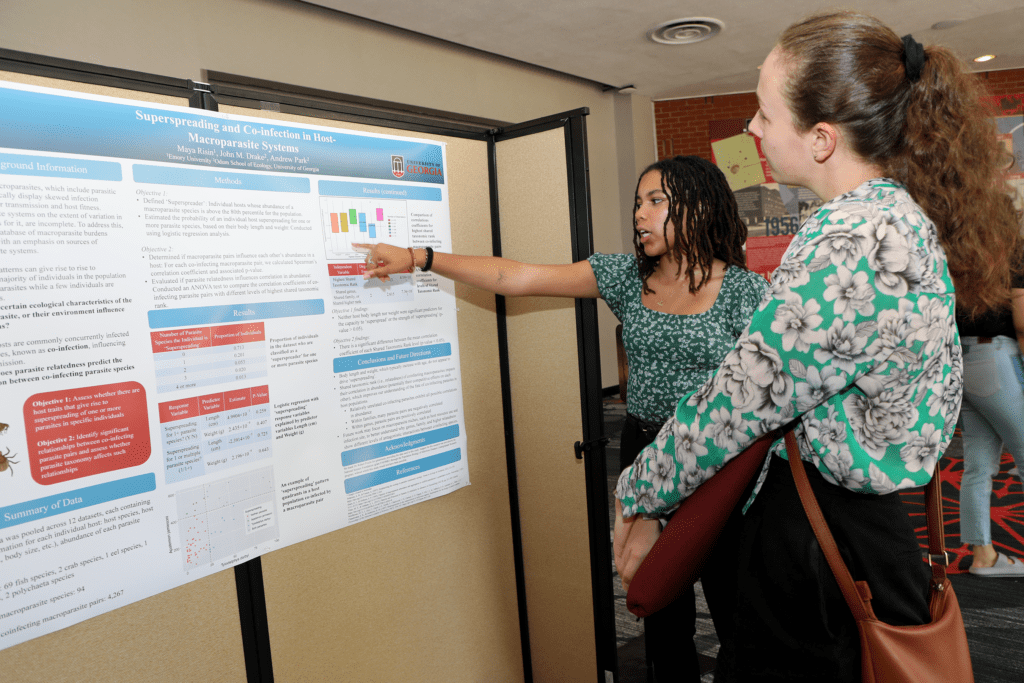

For the students enrolled in the program, a typical week consists of 32 hours of research and another eight hours of program activities. Student-led research projects in 2023 addressed topics ranging from detecting patterns of influenza-A virus variants circulating in wild birds to experiments testing how fish predators affect the transmission of fungal parasites in water fleas (tiny aquatic crustaceans). Computational projects analyzed large datasets for evidence of superspreading in parasitic worms and modeled how environmental variation affects the transmission of mosquito-transmitted diseases. Faculty mentors came from five different schools and colleges on campus, including veterinary medicine, public health, arts and sciences, forestry and natural resources, and ecology.

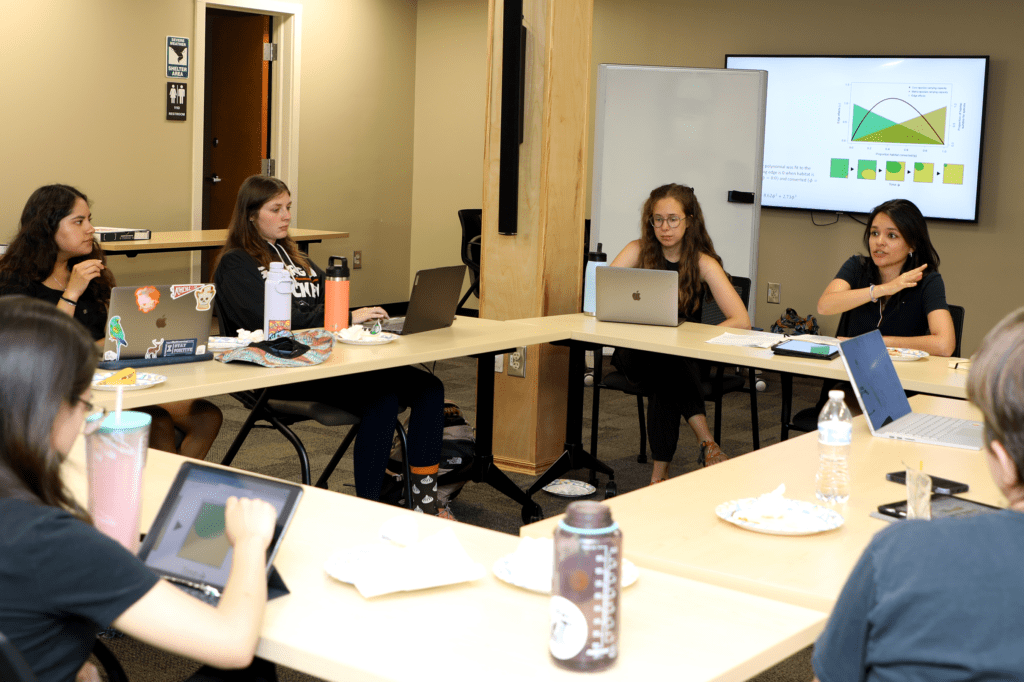

Maya Risin, a third-year student studying biology and environmental sciences at Emory University, said the program offers a level of independence and autonomy not found with other research experiences.

“This is the most independent research project I’ve ever worked on,” she said. “I meet with my mentor once a week, which was much less than I expected, but it’s been great to problem solve on my own and test myself as a researcher.”

Expanding universes

The program’s 2023 cohort included nine students enrolled at colleges in Georgia, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Utah, many of which cannot provide similar research opportunities.

“This program offers something that our schools don’t offer,” Risin said. “It’s definitely a unique experience, and I think a lot of the other REU students agree that this is an opportunity we wouldn’t have at our home institutions, which is why it’s so important to us.”

Sonia Altizer, current program director and Martha Odum Distinguished Professor of Ecology, spoke to the importance of providing students with research opportunities.

“For a lot of these students, if they don’t have these opportunities, it can be really difficult for them to break into advanced graduate programs and to make the connections they might need to do research,” she said. “It’s really important to bring students here to campus in a thematically focused program to be able to get that hands-on research experience, and then to also provide professional development and mentoring which allows them to envision potential careers in scientific research.”

The program aims to challenge and hone students’ abilities as researchers. When part of Adekunle’s experiment failed to produce results for several weeks, it challenged her perspective of the scientific process.

“I like to think I have always been a successful person and have always been straightforward in what I’ve wanted in my academic career,” she said. “So to have something not work for the first six weeks of the program, it’s kind of hard. But it definitely taught me to appreciate the whole process and not just getting results.”

Ecology assistant professor Alex Strauss, co-director of the program and a faculty mentor, also spoke to the challenges of completing a research project in such a short period of time. “It’s really hard to squeeze a meaningful research project into nine weeks,” he said. “We’re learning new skills. We’re often troubleshooting new methods. But I think we do it successfully.”

The program has illuminated the collaborative nature of science for students. “Hearing my mentor say, ‘Well, I’m not an expert in this, we should call someone who is,’ has made me appreciate this collaborative nature and why it’s so valuable,” Risin said. “[Research] is about sharing our knowledge, and if you come from a perspective where you think you know everything, you won’t go far.”

Academics are people too

Humanizing science has been instrumental in facilitating relationships between students and their mentors, one of the most important aspects of the program. “I think it’s really important to show the students that we’re just people,” Strauss said. “We’re very approachable and sort of humanizing all of science, which I think is important for students.”

From the student perspective, the program’s approach to mentorship has been useful. “I don’t really see [academia] as a hierarchy anymore. The professors I met at Odum are so humble,” Risin said. “They’ll admit when they’re wrong and put any ego aside because at the end of the day, the project is more important. Seeing that has made me appreciate them a lot more.”

Adekunle’s faculty mentors were instrumental in shaping her experience. “My favorite part of the program is really the people,” she said. “I was in a rough place with science and my degree and knowing what I wanted to pursue. But being in this environment with so many people who are willing to help… It doesn’t even matter what I would ask about. If they didn’t know the answer, they found somebody that did. I really love the people here.”

Students in the program could also turn to Katie Schroeder, a Ph.D. student in ecology who oversaw much of the REU programming. Schroeder met one on one with participants throughout the program, discussing everything from solving research issues to applying to graduate school to finding fun weekend activities in Athens.

“Because we met throughout the entirety of the program, I really got to see the students grow in their confidence and project expertise,” she said. “In our first meetings, we talked about how they were starting to learn about their projects and meet their research labs, and by the end of the semester, they were all teaching me about the exciting, novel results they had found.”

The students also form relationships with each other. From movie nights to field trips to Waffle House, they become close during the nine weeks of the program, rooming together in Rutherford Hall and exploring Athens and the UGA campus. “It’s kind of nice for the people who haven’t been to Athens, we’re just kind of figuring it out together,” Risin said.

By the end of the program, students are equipped with skills to conduct research in infectious disease, have formed valuable relationships with their mentors and each other, and have gained a broadened perspective of ecological research. Students with experience in computational and experimental approaches to infectious disease research are of growing importance, according to Altizer.

“People know that infectious disease emergence and pandemic spread are in many ways driven by environmental change. Research in the study of the ecology of infectious diseases is more important today than ever before,” she said. “Being able to offer students hands-on experience with the tools, techniques and the expertise they might need to make contributions to the field is something I’m super proud that this program can offer.”