Regents’ Professor John Drake of the Odum School of Ecology and director of the Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases (CEID) is building a Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infectious disease model to explain how this virus is expected to spread after it is introduced into the United States.

Where a domestic outbreak begins and how quickly JEV spreads through human populations and the U.S. pork industry is a concern.

JEV is the leading cause of viral human encephalitis cases and deaths in Asia and Oceania, and each year, up to 175,000 people are infected when bitten by an infected mosquito. Although the majority of infections are either asymptomatic or result in mild discomfort, 1% or fewer cases will result in encephalitis, and the modeled global estimated case fatality rate (CFR) is 14%. Annually, the majority of cases are reported in China and India.

Drake’s goal is to understand and predict JEV’s movement across the U.S. over weeks or months after a potential introduction. One of the expected outcomes of this project is to help public health authorities and pork industry veterinarians understand how a JEV epidemic might be thwarted. The 2022 Australian JEV outbreak that rapidly appeared in commercial swine operations across the eastern half of the country that resulted in the Australian government declaring a Communicable Disease Incidence of National Significance led to this project.

“In January 2022, commercial pig farms in eastern and southern Australia began reporting about aborted fetuses and stillborn piglets,” said Drake. “These and other physical malformations are signs of JEV infections in pregnant sows. On the last Friday evening in February, JEV was confirmed in domestic swine herds in New South Wales and Queensland. A short time later, JEV in farms in South Australia and Victoria was also identified. The first human JEV infection was identified in Queensland on March 3. What was surprising about this outbreak was that it erupted throughout the country where JEV had not been previously detected.”

The 2022 Australian JEV outbreak infected 45 people and killed seven. Over 80 commercial swine farms reported infections, and the epidemic impacted 60% of the industry.

Before this epidemic, JEV had been isolated to the Australian islands in the Torres Strait and on the Cape York Peninsula in northern Queensland. One of the questions that Drake and his colleagues need to answer is how the virus spread southward.

“We know that the first human case and death from the 2022 outbreak actually occurred in February 2021 on the Tiwi Islands north of Darwin,” he said. “The Tiwi Islands are about 700 km west of the Cape York Peninsula where previous JEV cases were reported. The virus that spread from the Tiwi Islands into the interior of the country, including South Australia and Victoria, is genetically similar to a JEV virus isolated in Bali, Indonesia, in 2017. JEV viruses that have been circulating on the Cape York Peninsula originated in Papua New Guinea, and they did not contribute to the 2022 outbreak.”

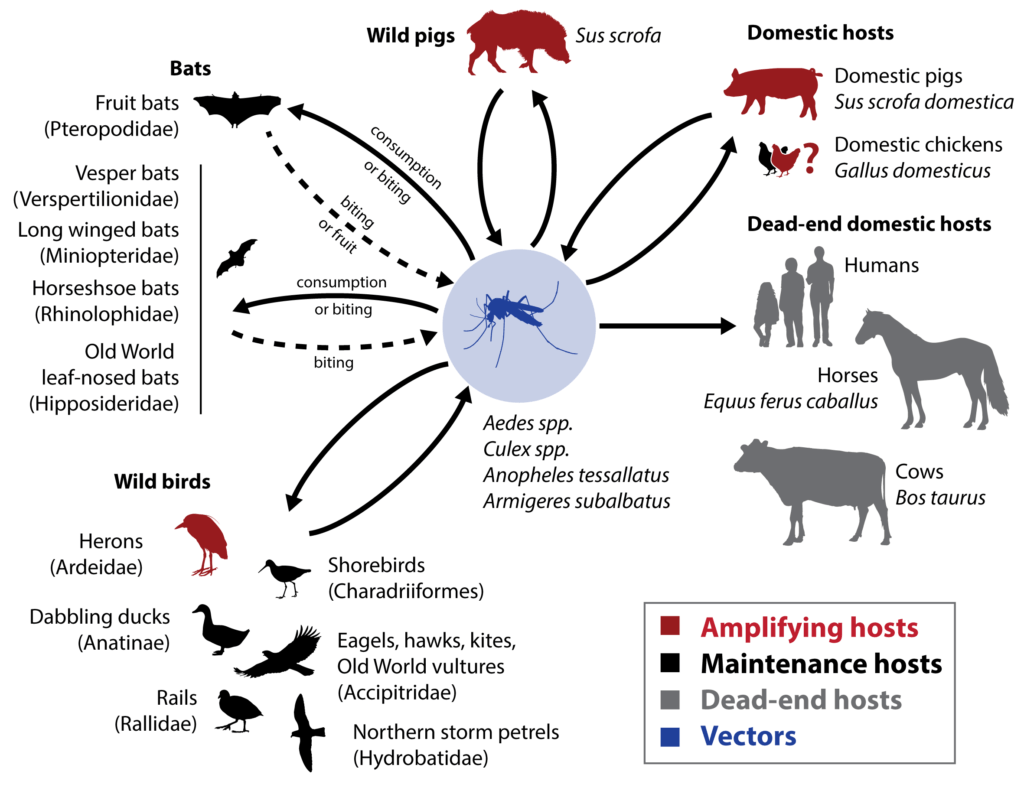

JEV is maintained in nature in a complex cycle that includes animal reservoirs, mosquito vectors and animal amplifying hosts. Animal reservoirs include herons and egrets that can maintain an asymptomatic level of infection and are able to infect biting mosquitoes. Mosquito vectors feed on infected animals and transmit JEV to other vertebrates including bats, birds, cows, chickens, dogs, horses, humans, pigs and wild boar. And amplifying hosts are animals that produce very high bloodstream viral loads when infected and are able to easily infect biting mosquitoes. Domestic pigs and wild boar are important JEV amplifying hosts.

Cows, horses and humans are considered dead-end hosts. Although JEV infections do occur after a mosquito bite, bloodstream viral loads are insufficient to infect feeding mosquitoes, and the cycle stops.

Understanding the roles that birds, mosquitoes, domestic and wild pigs, as well as other potential wildlife reservoirs have in JEV’s natural cycle is crucial for outbreak response and preparedness. Once an Australian JEV model has been developed, it will be applied to the ecology of the U.S. to simulate JEV’s spread across the country.

Drake is working with Natalia Cernicchiaro, associate professor at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University, and researchers at USDA National Bio and Agro-Defense. Cernicchiaro and her USDA colleagues are modeling how JEV may be imported into the U.S. from Australia or other countries including China.

Drake has developed numerous infectious disease models that explain how other viral pathogens spread after a spill over from wildlife into humans, including the 2013-2015 West African Ebola outbreak that infected over 28,000 people and killed more than 11,000. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, he created several models that showed how three human mobility behaviors influenced the spread of SARS-CoV-2 here in Georgia and across the country. However, modeling JEV is a unique opportunity for him.

“I have been very interested in modeling infectious diseases that are transmitted by mosquitoes that impact people and livestock,” he said. “JEV is just one of several important diseases that affect farmed pigs, and considering the size of the U.S. pork industry, I am happy to help industry learn how our models can be used to develop contingency plans in the event of an outbreak. I am grateful to both Natalia and USDA Agricultural Research Service for their collaboration and funding to research and build a JEV model.”

The CEID’s research and development of a JEV spatial interaction model is funded by a Kansas State University subaward (#A24-0079-S001).