HorseShoe Bend, an ecological research site located near the University of Georgia’s main campus in Athens, has a rich history dedicated to scientific discovery, teaching, and training focused on ecosystem processes and the natural environment.

As one of the Odum School’s primary research sites, HorseShoe Bend was founded at the confluence of opportunity and initiative following its acquisition by the university in 1928. Although the College of Agriculture originally used this land for dairy cattle grazing, their need for pasture outgrew the available space. This presented an opportunity for Eugene Odum, UGA professor and inaugural director of the Institute of Ecology, to develop a staging area for long term ecological research. In 1965, Odum secured permission to begin ecological experiments at the 35-acre field station, and in 1984 the site was officially assigned to the Institute of Ecology.

Characterized by a mixture of upland fields and forest dominated by oak, pine, and river birch, HorseShoe Bend was named after its natural topography, as the site is bordered by a deep bend in the North Oconee River.

Early research

Some of the earliest ecological research at HorseShoe Bend focused on the effects of a common pesticide on the above-ground community of small-seeded grasses, insects, and small mammals. Gary Barrett, then a graduate student working under Odum’s direction, launched this work in 1965. Initial studies established field plots that were used in subsequent agroecosystem research, including effects of fertilization on secondary succession. Later, as the first Odum Chair in Ecology, director of the Institute of Ecology from 1994-96, and director of the field station for nearly 20 years, Barrett studied landscape ecology and small mammal population dynamics, including species interactions between golden mice, white-footed mice, and southern flying squirrels.

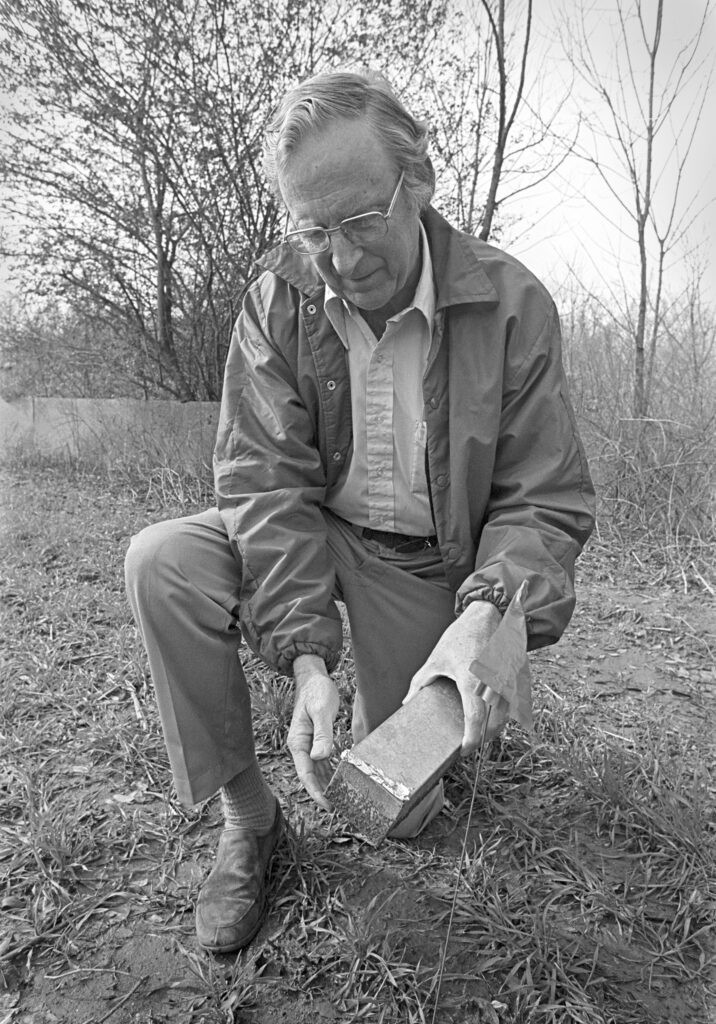

For more than five decades, HorseShoe Bend has afforded ecologists the opportunity to conduct large-scale field perturbations. Soil ecologists David Coleman and Dac Crossley, professors emeriti in the Odum School, created plots to study how no-tillage versus conventional tillage affects carbon storage and soil microbes. Studies conducted during the 1980s and 1990s at the site allowed Coleman and Crossley, together with Prof. Emeritus Paul Hendrix, to measure nutrient turnover and the many organisms that participate in this complex process. Coleman described how this site was one of the few locations for research focused on how tillage practices affect ecosystem function, and also provided active learning opportunities for numerous UGA graduate and undergraduate students.

“Rather than having students read about somebody doing an experiment, they got to actually do soil respiration measurements here,” said Coleman.

Field experience within reach

Present-day Odum faculty underscore the continued importance of this site and its facilities for long-term ecological research and experiential learning.

Two buildings in the upland forest habitat offer research, classroom, and office space, and are frequently used by introductory- and upper-level ecology courses. A pole barn and a cement block house provide storage in the lowland field. Trails run along riparian corridors, the north- and south-facing slopes, and old field habitats throughout the site. Odum School researchers and students continue to develop new facilities for training and scientific discovery at HorseShoe Bend.

“Recently it’s become much more heavily utilized for our ecology classes and for our research labs, and we are seeing a resurgence of ecological research and teaching at the site,” said Sonia Altizer, Odum School interim dean and Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Ecology.

Kait Farrell, PhD ’17, the undergraduate lab coordinator for the Odum School, described a typical research experience for students as a process of visiting the site, understanding its ecology, and developing a question that can be answered throughout the semester, with frequent data collection from HorseShoe Bend made possible by its convenient location within walking and biking distance from main campus.

“Students like it because it puts the course content into practice,” Farrell said.

Asking new research questions

Altizer described this research site as a rare gem because it allows students and faculty to conduct extensive and long-term experiments in close proximity to main campus.

Starting approximately four years ago, Altizer’s students set up flight cages in the upper and lower fields to conduct outdoor experiments to test how monarch butterfly migratory behavior is affected by environmental variables. In addition, a recent graduate student conducted research at the site to explore whether monarchs use social information (cues from other individuals) in their migratory orientation.

HorseShoe Bend has hosted numerous other projects in recent years, like studies of the invasive Joro spider (read the story), authored by Odum faculty member Andy Davis and undergraduate Benjamin Frick. Davis also teaches an Ecological Physiology class at the site, demonstrating the versatility of this location for the support of student learning.

Ongoing work by Assoc. Prof. Jackie Mohan and Paul Frankson examines belowground forest ecosystem processes such as soil respiration and nutrient cycling at the site.

Recently-hired faculty like Takao Sasaki have launched new projects at HorseShoe Bend, boosting its visibility. Sasaki used the facility to house homing pigeons, studying how they make decisions by scanning information among their group mates. Sasaki, along with his students, raised pigeons in a loft at the site and released them several miles from home to study their flight patterns. Due to the site’s versatility and space, Sasaki was able to conduct his experiments in a natural environment.

“If you want to study the river, it’s there. If you want to study the forest area, it’s there. Or if you want to study homing pigeons like I do, that’s possible too,” Sasaki said.

Alex Strauss, who joined the faculty in fall 2020, researches plant and aquatic infectious diseases.

“I am really excited about just the potential the HorseShoe Bend site holds for a number of different projects,” he said.

One of these studies examines fungal pathogens that infect the leaves of tall fescue, a common forage grass found in the Southeast. Strauss explained that Coleman and Crossley’s earlier study of ecosystem impacts of tillage vs. no tillage resulted in a field of tall fescue, perfect for his current work.

Rebuilding for the future

Faculty member John Wares has stepped up to the challenge of rebuilding the trail network at HorseShoe Bend, critical for maintaining the area. Wares, a professor with a joint appointment in Ecology and the department of genetics, has used his background in trail advocacy to repair old trails and construct new ones. This work began as a means of encouraging people to check out the site during the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, at a time when most classes and activities had shifted online.

“From my point of view, it is starting to regain some visibility as a really close field station for us,” said Wares.

Faculty colleagues and students joined Wares in a three-day trail restoration project, which improved the site’s utility. This work brought accessibility back to the site and boosted the number of projects that can use what HorseShoe Bend has to offer.

It is clear that HorseShoe Bend has a long history with the university and the Odum School of Ecology, and, with its resurgence of research activity, it continues to be a crucial academic resource. Its proximity to campus, natural ecology, and overall versatility make this valuable field site an exciting opportunity for faculty and students to engage in an array of diverse projects in ecology. The confluence of opportunity and initiative in the ’60s laid the groundwork for this area to become a contemporary nexus of creative ecological research.

With the continued work of Odum faculty and students, the future of HorseShoe Bend as a multi-use field station is even more promising.