It’s that time of year. The buzz of mosquitos is in the air, and people wonder, “Where are these bloodsuckers coming from?”

Unfortunately, many of them may come from habitats we created.

Mike Newberry (PhD ’25), a recent graduate of the University of Georgia’s Odum School of Ecology, spent two years studying the numbers and types of mosquitos in a swath of northeastern Atlanta, counting the insects and their larvae to better understand how we create micro-climates that encourage mosquitos.

Mosquitos are a nuisance, but they also can spread diseases like West Nile virus, a risk that ramps up during August and into the fall.

“The peak for West Nile transmission begins in late summer, and people aren’t aware that they are more vulnerable then,” said Natasha Agramonte, an entomologist and mosquito control coordinator for DeKalb County Public Health. “This is not the time of year to let your guard down.”

Mosquitos can thrive in the city

People often think mosquitos are worse in wilderness, but in-town properties have mosquito habitat, too, particularly if neglected landscaping allows water to pool.

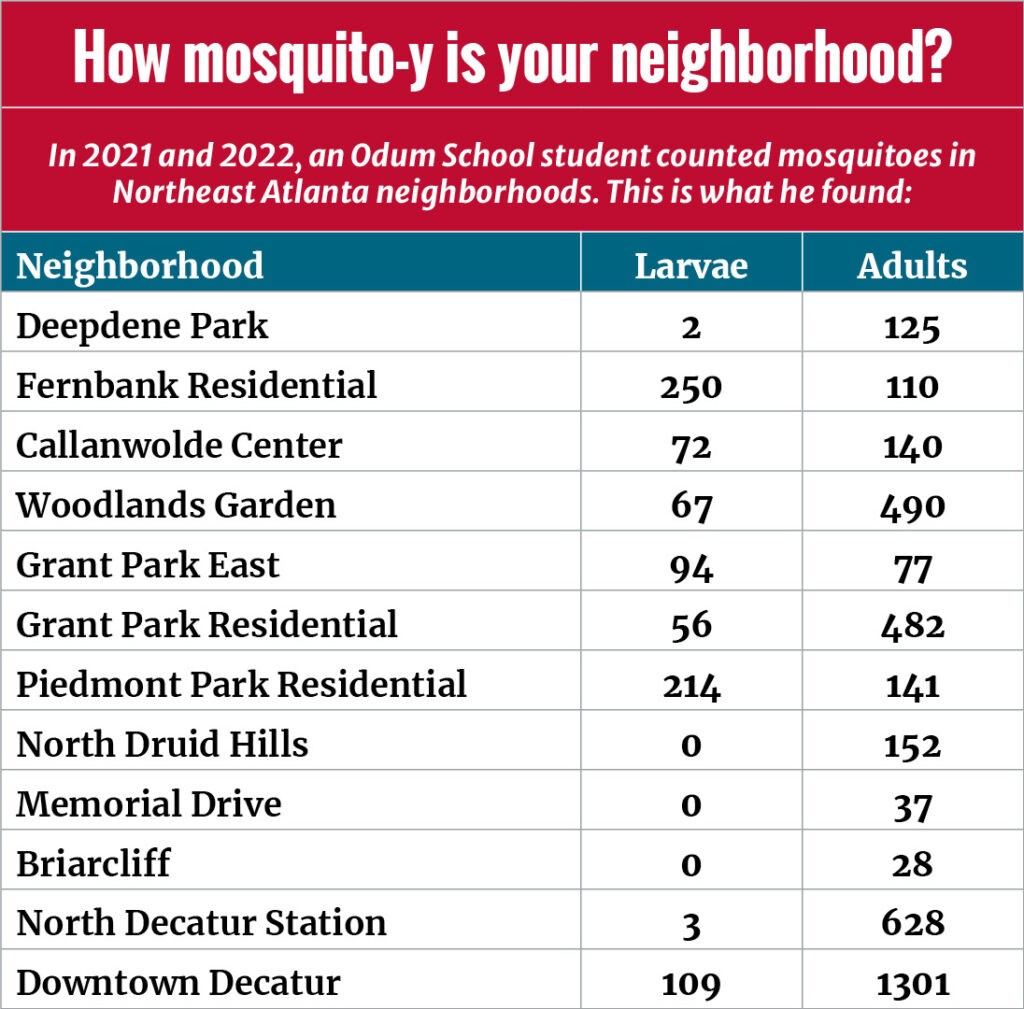

Newberry surveyed mosquito populations in 12 Atlanta neighborhoods—all inside 285—from June to October over 2021 and 2022. He started by approaching landowners and asking permission to monitor their land for mosquitos.

“I really wanted the breadth of urban to suburban land use, but also want to stay within the Perimeter,” he said.

He chose a shopping center, a school, suburban neighborhoods and two pocket parks to get ground covered with pavement or grass, as well as blistering sun and cool tree cover.

Climate sensors continuously recorded the temperature and humidity, while Newberry returned every 30 days for two years during the most mosquito-y months to count insects and their larvae. To collect adult mosquitos, researchers use dry ice and octenol, a volatile alcohol that humans emit in their breath and sweat, to attract the insects into traps. Since larvae live in water, they are a little easier to find than their adult forms.

In the end, Newberry considered the amount of impervious surface, the canopy cover, relative humidity and temperature, as well as how many mosquitos and larvae he found.

“It is interesting that sometimes the best sites for larval habitat might not be the best sites for the adult. Warmer temperatures might speed up adult mosquitos’ reproduction, but it also might dry up larval habitats,” he said.

Economic downturns can be a boon for mosquitos, when foreclosures leave swimming pools unmaintained, but Newberry found that affluent homeowners with manicured lawns might also generate mosquito habitat.

“Other studies also show that economically privileged areas with a lot of landscaping and flowerpots—people who put a lot of care into their yards—also could counterintuitively drive up the mosquito populations,” he said. “Humans create the pools of water for larvae to thrive while warm temperatures drive up the numbers of adult mosquitos.”

In Newberry’s mosquito census, the highest population—both of adults and larvae—was in downtown Decatur, where he found a mosquito-ridden flowerpot while counting larvae. The private park, Woodlands Garden, and Grant Park neighborhood also had high numbers of mosquitos.

Humans breed mosquitos

Agramonte’s experience mirrors Newberry’s findings. Many of the people who seek her help with a mosquito problem are unintentionally creating habitat for the insects.

“Many of the calls I get are from people who don’t know that they are growing their own mosquitos,” she said. When she walks around with property owners, they often are surprised that the source of mosquito larvae is on their property.

The mosquitos that live in Georgia don’t travel very far on their own—maybe as far as 100 meters—so finding the source usually isn’t difficult. Keeping the numbers low is important, not just for sanity, but to keep disease under control. The more mosquitos there are, the more likely they will spread a disease.

“Mosquitos have been part of Georgia’s history for a long time,” Agramonte said. “There are diseases that are no longer here – and we don’t want them back – as well as diseases that aren’t here yet and be hope never to see.”

Viruses like West Nile and Zika made news when they arrived in the U.S. over the past two decades, and now an old disease may be returning.

At one time, dengue was thought to be eradicated from the U.S. mainland, but in recent years locally acquired cases have been reported in several Southern states, including Florida, Texas, Arizona and California. Most people who get dengue will not have symptoms, but some will develop high fever, headache, body aches, nausea, and rash. Dengue fever kills about 1% of people who develop illness, even with excellent hospital care.

Earlier research from the Odum School found that the risk of dengue transmission in Athens-Clarke County might be twice as high as the risk in rural areas because of higher temperatures from a heat island effect.

“It’s really tough from a planning standpoint. We know impervious surfaces make an ideal environment for human-adapted mosquito, but that’s also key to how we develop our urban environment,” Newberry said. “We could encourage more canopy cover, but that might also make a better environment for larvae.”

People who live in an urban or suburban environment should watch their yards, Newberry advises, to root out standing water or use anti-larval cakes that contain Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti), a naturally occurring bacterium that is toxic to mosquito larvae but harmless to other organisms.

“The important thing I hope people understand is that you could have just one bucket of water on your property that harbors 200 to 300 larvae and, if those adult mosquitos travel 100 meters, you could impact several of your neighbors,” he said.

“A relatively small oversight on your part could be major source of mosquitos for your entire area. That not only can impact your home and make you unhappy, it impacts someone three houses down the street.”