Overharvesting, disease and pollution decimated Chesapeake Bay’s oyster population, and it’s taken years of dedicated restoration projects to see progress in the recovery of this ecosystem engineer. Now, researchers at the Odum School of Ecology are studying oyster disease in Georgia.

Nature’s unsung architects, oysters provide structured reef habitat and shelter to valuable crustaceans and fish along the entire Georgia coast. Oysters are also voracious filter feeders and improve water quality by removing excess nutrients and suspended sediment from the water column.

But Georgia’s oysters are diseased—and at disquieting rates.

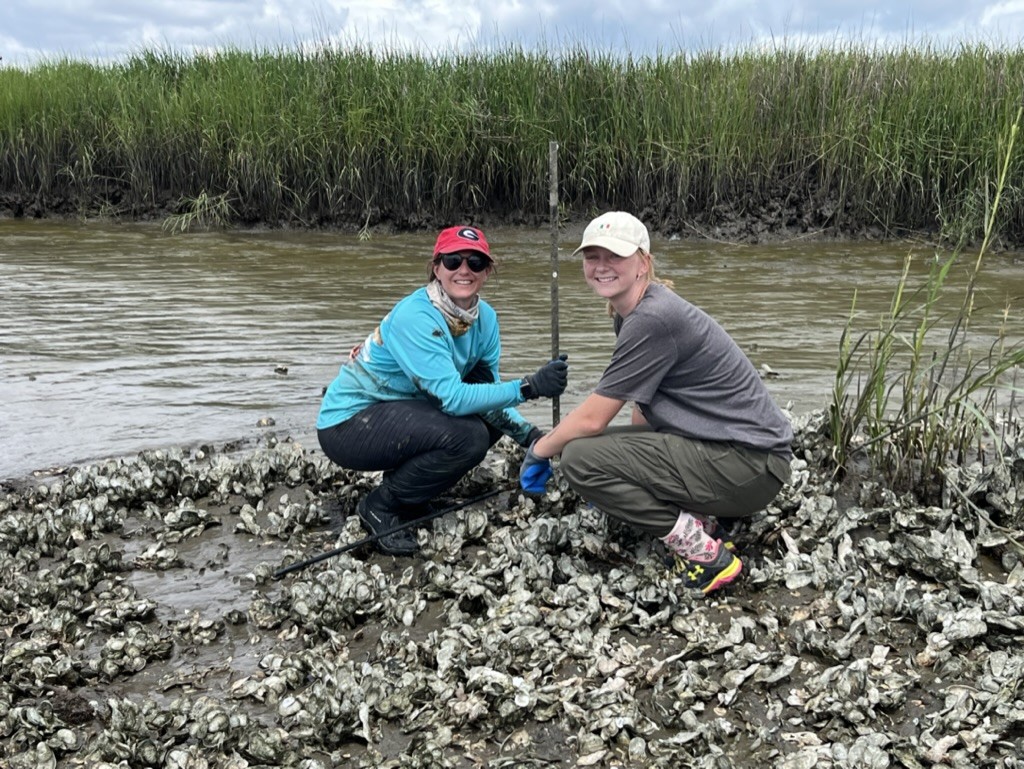

“We’re seeing at the lowest about 45% of the oysters are infected on a single reef, with upwards of 90% in some areas,” said Shelby Ziegler, a postdoctoral associate at Odum who helms the ongoing project alongside Jeb Byers, associate dean for research and operations and UGA Athletic Association Professor. The two have collaborators at Georgia Southern—John Carrol and his student Will Atencio—and oversee a group of undergraduate researchers.

But despite the widespread sickness, oyster reefs remain healthy in Georgia, for now. They’re plentiful and show distinct structural complexity, two major predictors of wellness in oysters.

As a part of their research, Byers and Ziegler are trying to account for the discrepancy between the degree of disease and the largely healthy reefs. They’re looking into several possibilities.

“One hypothesis is that this disease is not having a high mortality effect on our oysters here,” said Ziegler. Some strains of the disease impacting oysters may be less lethal than others.

But alternatively, bad news may simply be slow to arrive. “It could just be that it’s taking a long time to kill them,” explained Byers.

One thing they’re sure of: The disease prevalence is alarmingly high. The team is trying to uncover why. And critically, they want to know if the myriad of ecosystem services performed by oysters are impacted.

A linchpin pulled: The impact of oyster disease

“Oysters are important not only because they’re a food source,” Byers pointed out. “They are also solidifying the bank and preventing it from eroding. If you have a disease in a species like this, that’s so pivotal to the system, it would be very critical to know if it’s compromised.”

They’re going to great lengths to find out if it is. They have sampling sites at 24 oyster reefs, systematically spanning the whole Georgia coast—from Savannah to the Florida border.

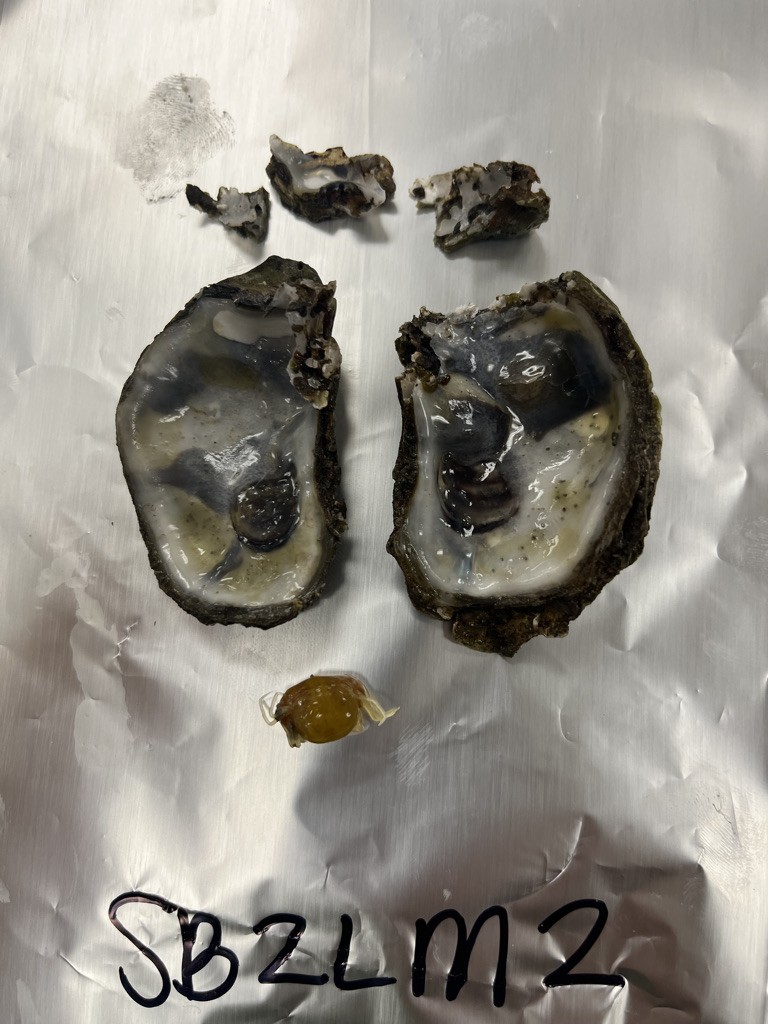

While in the field, they sampled anywhere from three to six reefs a day, excavating a quarter meter quadrat—a small, randomly selected sample of habitat—a set distance from the top of the reef. Returning to the lab with all the material in the sample for processing, they then conducted a comprehensive survey. Besides running PCR testing to measure disease prevalence, they measured oyster size and distribution, counted up to 2,000 oysters per quadrat, and looked for parasites like boring sponge, mud blister worms and pea crabs, among other tests.

They’ve also placed temperature loggers at each site and inserted devices to measure oyster recruitment, or the integration of new oysters onto a given reef.

All this, the researchers hope, will give them a window into how oyster disease is impacting the species—and the state itself.

With a budding oyster aquaculture business, Georgian economists and oystermen and women have a vested interest in the researchers’ eventual findings. Though the diseases impacting eastern oysters can’t harm humans, they can potentially harm harvests, since the diseases have been linked to previous oyster mortality events.

The Department of Natural Resources, too, wants to know more about oyster disease in the state—the project is funded by GADNR’s Coastal Incentive Grant. And given oysters’ critical role in marine habitats, several coastal conservation groups are interested in the answers Ziegler and Byers find.

And ultimately, when it comes to water quality, everyone is a stakeholder.

“Water quality is an important issue, especially along our coastlines, not only for human use,” said Ziegler. “Potentially, if filtration is impacted by these diseases, we might see a decrease in that overall water quality and the provisioning of habitat for other organisms that are economically and ecologically important in our system.”