Martinique Edwards, BS ’18, is an ORISE (Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education) Fellow at the CDC. She talked with Ecology major Sam Patterson, AB ’24, about her path to doing coronavirus research, how an ecology background has helped her career, the importance of keeping an open mind, and parkour. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sam Patterson: How would you describe what you do?

Martinique Edwards: I’m doing an ORISE (Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education) Fellowship at the CDC in Atlanta, working on coronavirus—not SARS Coronavirus 2 that’s causing COVID-19, but a genetically similar coronavirus called OC43—and studying its persistence on surfaces.

SP: What was your post-graduate path like after graduating from the Odum School in 2018?

ME: I followed that by doing a master’s in environmental health science at UGA just next door. Then I kind of switched gears and did a year of AmeriCorps VISTA at the Athens Community Council on Aging. I worked on food distribution and a little bit of community gardening. I got to work with a different population of people outside of the university and that was a cool experience for me. From there, I knew that my position in AmeriCorps was only temporary, and I ended up receiving an email from my master’s professor, Dr. Erin Lipp, and she said, “Hey, there’s this position that just opened up at CDC.” For my master’s research, I worked with antibiotic resistant bacteria cultured from rivers and streams, and that background experience really helped out with getting me into this research position at CDC.

SP: What does a typical day at work look like for you (if there is such a thing)?

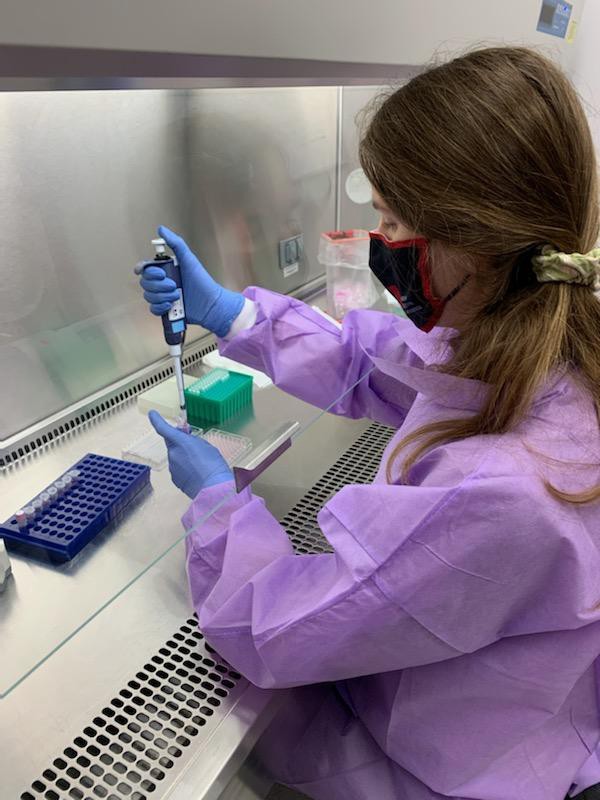

ME: My workday is mostly lab based. We’re doing a bunch of experiments working with live viruses, to see how they react to different environments. We let them sit in an environmental chamber at a set temperature and humidity for anywhere from three hours up to two weeks, and at different time points we process them and see how much live virus is there. Our aims are really to apply this to a hospital setting; if you think about the respiratory viruses being aerosolized in the air, they could be depositing onto surfaces and drying there, and we don’t really know too well what happens to those viruses after that. Like if somebody were to touch their hand on the surface, how much of that viral load gets on their hand? How does that all lead to infection for somebody? That’s still pretty much a big question mark and so we’re just trying to figure out what we can do—basic research.

SP: What influenced you to go down a more infectious disease focused path of ecology, rather than something like studying ecosystems?

ME: Honestly, I still feel like I’m very open minded, I could go multiple different directions. Ecosystem health and infectious disease ecology definitely have seemed to have stuck with me. When I was an undergraduate, we were working with water systems trying to detect bacteria that could be pathogenic in the water systems. And then we started taking a step back and thinking, well why is that bacteria there in the first place? Is that from sewer pipelines leaking? Could it be agricultural runoff? And so, I guess because of my ecology background at UGA, I’m constantly thinking about how everything’s interconnected and why things are the way they are.

SP: Was there anyone you’d see as a mentor at Odum, or someone who helped guide your path?

ME: I took Dr. Amy Rosemond’s freshwater ecosystems class, which just made me so, so excited about the whole field of research. Her class was very hands-on. My research partner and I ended up studying how disturbance of the sediment of streams would affect fecal coliform levels in water. It’s really cool to be able to learn about fresh waters in her class and then go out there during that same semester to conduct your own research.

SP: As a recent graduate, what is some advice that you’d give a current undergraduate student?

ME: I’d say to keep an open mind, and to ask questions. Through high school we tend to learn directly from what’s in the books and we don’t really question why things are the way they are. But in ecology, you learn to see things through the eyes of multiple organisms, at different scales, whether micro scale or all the way up to ecosystem scale.

Also, if you start to feel that life isn’t headed in the direction that you want, take some time and self-reflect and maybe look at the situation in a different light. Perhaps by taking a step back you can see, oh, well, this is something new I could introduce into the situation, or maybe this really isn’t what I want to do after all. Don’t be scared to step away, as a break or even to try something totally new.

SP: Outside of ecology, what were some of your favorite things to do on campus?

ME: I got involved with a few club sports, cross country and ultimate frisbee, but I ended up sticking with parkour. [Parkour combines elements from running, climbing, gymnastics and other sports using features of the urban landscape as an obstacle course.] There’s a very small group, and it’s open to the public. We kind of feel like big kids, but it’s good to keep your mind open and interact with our environment in a different way from how we might otherwise.

SP: To close: has there ever been an experience you’ve had with a wild animal that has stood out to you in any way?

ME: I was actually just thinking about this the other day. I was in the Florida Keys assisting with some coral reef research. I was snorkeling and free diving, and I went underwater about six feet deep and saw what looked like a fallen mast of a sailboat. It was rusted and had holes in it. I started running my thumb around the rim of one of these holes, then before I knew it I saw a humongous eyeball, and a large set of teeth clamped down onto my thumb. It was a moray eel, I think, and it seemed to be just as surprised as I was. We locked eyes for a few seconds and then very slowly without blinking it released its teeth and went back into its hole. I was thinking, oh wow, what a cool experience. Of course my thumb was gushing blood, but it was a small eel, thankfully!